New Lake found below Siniolchu, a beautiful but unwelcome discovery

Melting glaciers have always been at the heart of the discussions on Global Warming over the last few decades. A recent study, published in the Nature Climate Change Journal [1], says that glacial lakes have increased by 50% in the last thirty years, deepening the risk for billions of people by exposing them to the threat of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs).

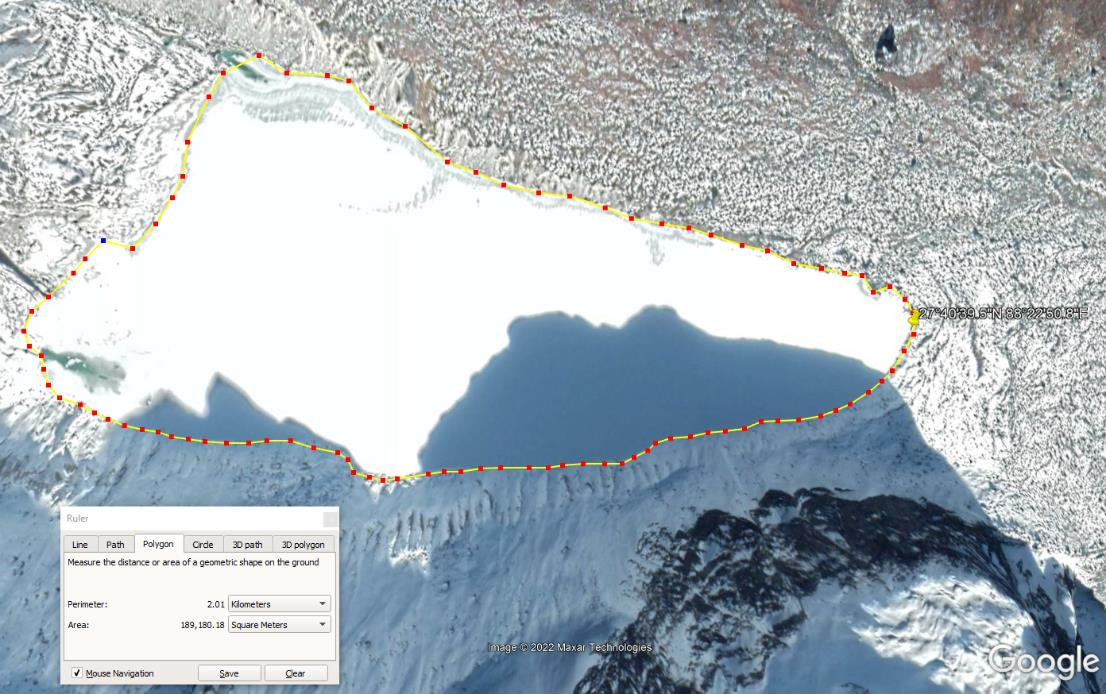

Recently, Indian climber and explorer, Anindya Mukherjee led a team in an exploratory expedition to the Temrong-Zumthul Phuk valley and glacier system, in North Sikkim, during May 2022, and found a large lake at the Zumthul Phuk Glacier at 3900m with an approximate area of 189,180 m2. Anindya documents this discovery of a new lake, and a detailed report of the same has been submitted to the statutory authorities of the Govt. of Sikkim, who authorized this expedition.

Mt Siniolchu and the Lake

While this discovery is an important contribution to the corpus of knowledge on geo-exploration and its relevant literature, it is also welcome news for the mountain adventure community and may attract numerous adventure enthusiasts to the valley in the future. But unfortunately it is also an unwelcome discovery, as it shows us in real time the grave threat posed by a threatened eco-environment.

Mr. Mukherjee says that, "based on our primary observations, we understand that it is a 'Moraine Dammed Glacial Lake' created by glacial retreat due to global warming and by the topographic depression of the terminal and the right lateral moraine of the Zumthul Phuk Glacier located due South-East of Mt Siniolchu."

Interestingly however, Anindya Mukherjee had done the first traverse [2] of the Zumthul Phuk gorge in 2014. During the trip, Anindya and his team had noticed a section of a water body, but as they were traveling to a different direction they couldn't determine the existence of the lake properly. But this time Anindya dedicatedly explored, evaluated and documented the lake.

Zumthul Phuk Valley

Lake on Zumthul Phuk Glacier (27°40'39.5"N 88°22'50.8"E)

A brief expedition summary

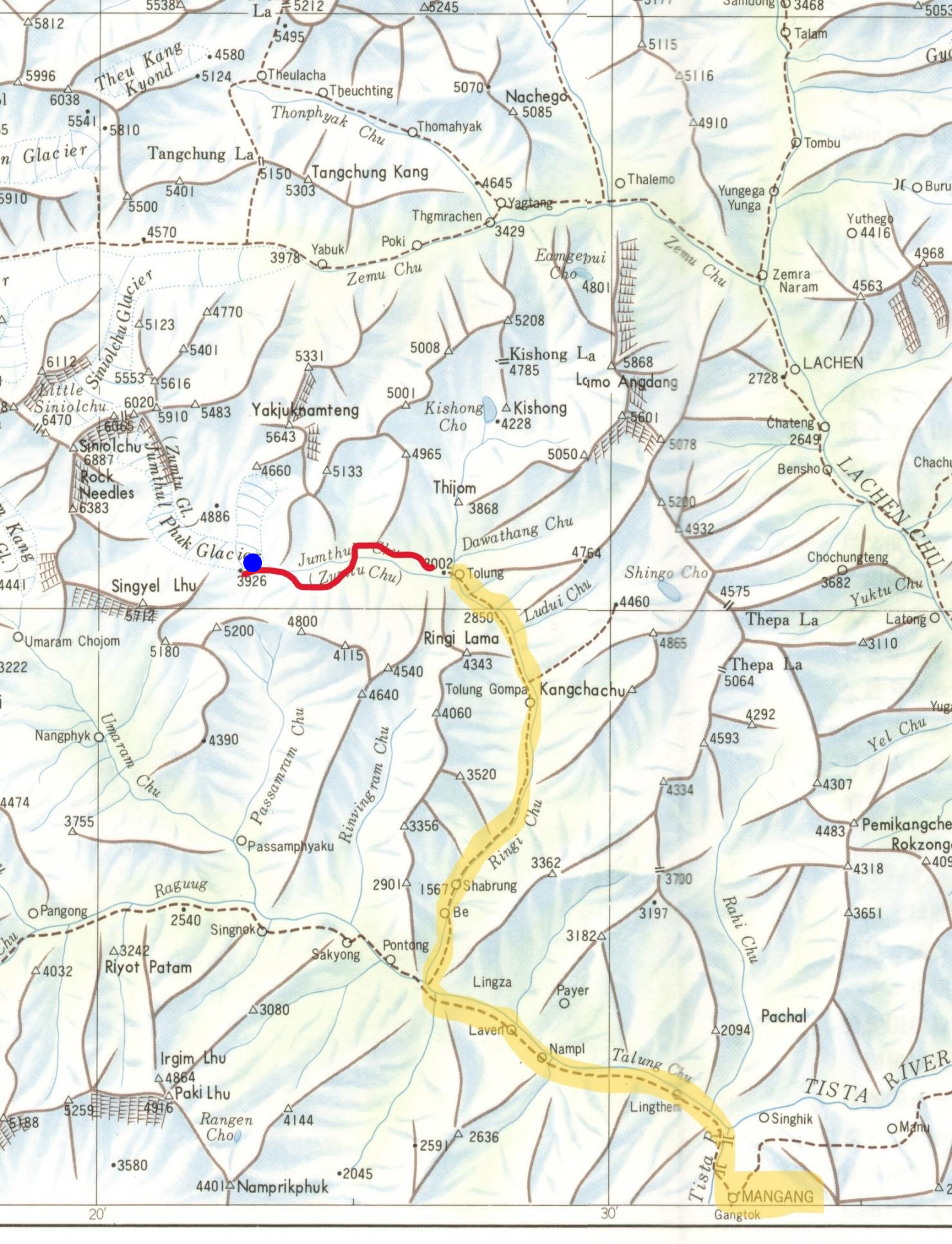

A six man team led by Anindya Mukherjee started their expedition from Gangtok on 24th April 2022. They reached the road head, Bay Village, on 1st May and trekked to Tholung. Next day, they reached Temrong camp. They needed to set up three more camps in the narrow river gorge to reach the Base Camp of Siniolchu on 5th May. Then they explored the Zumthul Phuk Glacier, discovering this Lake in the process. Finally, they returned to Bay village on 9th May.

Construction of the makeshift log bridge on Zamtu Chu

"It finally stopped raining on the dawn of 7th May and without losing time we all hurried to climb the settled terminal moraine of Zumthul Phuk Glacier and within an hour's climb we reached the crest of the moraine ridge and waited patiently for the fog to lift with the warmth of the rising sun. After an hour of waiting in nippy weather the warmth of the sun lifted all the fog and cloud off the grand South East Face of Siniolchu and an overwhelmingly beautiful lake appeared below its feet. All of us stood speechless for a while and felt thankful to have been able to witness this unforgettable sight. We felt that all our toil and struggle has now been rewarded and we were indeed blessed to have discovered this grand new creation of nature - the large lake of the Siniolchu's Glacier Zumthul Phuk. It was a feeling of completeness and it was now time for us to go back down to safety," Anindya Mukherjee stated.

Emergency Intermediate Camp on 4th may

Reaching at Base Camp site

30th April - Mangan to Bay village/12 Mile- Drive, transhipment at Mantam

1st May - Bay village to Tholung Gompa trek, 6 hrs hike

2nd May - Tholung to Temrong trek, 4 hrs hike

4th May - River/bridge camp to emergency Intermediate Camp trek - 6 hrs hike

5th May - IC to BC- 1 hr hike

6th May - bad weather, stranded at BC

7th May - visit Zumthul Phuk Glacier & Lake, trek back to River camp- 6 hrs hike

8th May - Trek to Temrong camp- 3hrs hike

9th May - Trek to Bay village

Highest point: 3900m-4000m

Location and measurements of the lake:

Co-ordinates: 27°40'39.5"N 88°22'50.8"EPerimeter: 2.01 km (1.25 mi)

Area: 189,180.18 m² (2,036,318.58 ft²)

Surface Elevation: 3900m to 4100m

Team Members: Anindya Mukherjee ‘Raja’(Leader), Phurtenji Sherpa ‘Lakpa’ (Ilam, Nepal), Mingdup Lepcha (Passingdong, Upper Dzongu, Sikkim), Sampan Lepcha (Sakyong, Upper Dzongu, Sikkim), Chhudup Lepcha (Sakyong, Upper Dzongu, Sikkim), Sonam Pentso Lepcha (Sakyong, Upper Dzongu, Sikkim) and Pema Chopel Lepcha (Sakyong, Upper Dzongu, Sikkim)

Yellow highlighted route/trail-old/traditional route. Red line- new line of exploratory route. Blue dot shows approximate location of the lake

Team members standing by the shore of the lake

Sikkim and Teesta Basin

Last year, in 2021, in a study [5] on the Teesta basin in the Sikkim Himalayas, which hosts numerous glacial lakes at high altitude, identified South Lhonak Lake as one of the largest and the fastest-growing lake with potential avalanche impacts in the future. The same study evaluates that "the future volume of the lake based on an ice-thickness approach is calculated to be 114.8 X 106 m3. This enormous volume of water in a highly dynamic high-mountain environment makes this lake a priority for GLOF risk management. Our results show that the GLOF susceptibility will increase due to the expansion of the lake towards steep slopes, which are considered potential starting zones of avalanches. These avalanches can create an impulse-wave when hitting the lake and are considered the most likely GLOF trigger for the South Lhonak Lake."

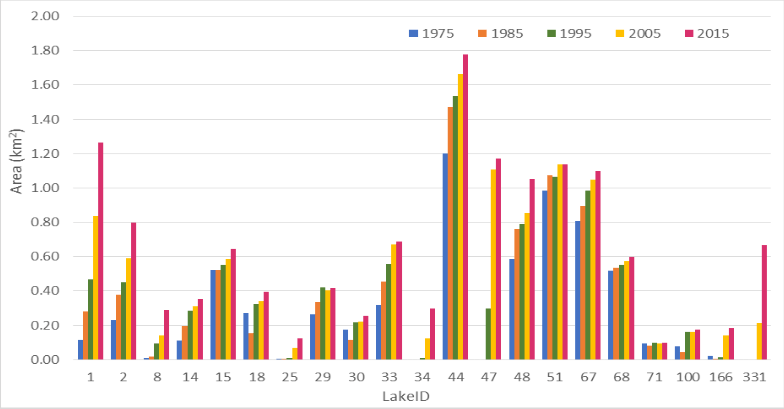

A study in 2017[3] has also found 21 lakes out of 472, which are susceptible to GLOF, all increased their area during the period of 1972-2015.

Areal change of lakes susceptible to GLOF between 1975 and 2015 [3]

The Global Scenario

Glacier melting has increased manifold in the recent times [1]. This has led to an increase in the number of glacial lakes and sea level rise. Glacial lakes are the source of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), and lead to disastrous floods, particularly in developing countries like South America, central Asia etc. However, some glacial lakes can have a positive impact as in producing hydroelectric power, being a reliable source of water and better regulated water flow. Around 1.9 billion people rely on glacial lakes for water supply.

The number and volume of Global glacial lakes have increased rapidly over the past few decades. In the 1990-1999 timeframe, a study [4] says 9414 glacial lakes covered approximately 5930 km2 of the earth's surface, which together contained nearly 105.7 km3 of water. As of 2015-18, the number of glacial lakes globally had increased by 53%, which is approximately 14393. The total area of the lakes had grown by 51% to 8950 km2 and their estimated volume had increased by 48% to 156.5 km2. The median lake and the largest lakes have also increased in size by approximately 3% and 9% respectively in the timeframe 1990-2018.

As a result of the increase in glacial lakes, the level of the oceans is also going up. The rise in glacial lakes led to an increase in 0.14 mm sea level in the timeframe 1990-1999 and a rise of 0.43 mm sea level in the timeframe 2015-18. From 2016, glaciers outside of Antarctica and Greenland lost 227±31 GT of ice annually which contributed to 0.63±0.008 mm/year sea level rise. Greenland and Antarctica lost 290±19 km3 and 147±6 km3 water equivalent per year from 2003-2016 respectively.

Zumthul Phuk Valley

Anindya Mukherjee

Photo Courtesy: Anindya Mukherjee

References:

[1] Shugar, Dan H., et al. "Rapid worldwide growth of glacial lakes since 1990." Nature Climate Change 10.10 (2020): 939-945.

[2] "ZUMTHUL PHUK GLACIER, EXPLORATION", American Alpine Club Publication, 2015

[3] Aggarwal, Suruchi, et al. "Inventory and recently increasing GLOF susceptibility of glacial lakes in Sikkim, Eastern Himalaya." Geomorphology 295 (2017): 39-54

[4] Jahan, Raunaq, et al. "Quantification of Geodiversity of Sikkim (India) and Its Implications for Conservation and Disaster Risk Reduction Research." Climate Change, Extreme Events and Disaster Risk Reduction. Springer, Cham, 2018. 279-294.

[5] Sattar, Ashim, et al. "Future glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) hazard of the South Lhonak Lake, Sikkim Himalaya." Geomorphology 388 (2021): 107783.